Telemedicine and emergency care: differences between UK and USA

In the United Kingdom and the United States, the use of telemedicine in emergency care stems from a very specific need: enabling qualified clinical decision-making precisely when speed and accuracy are critical. Assessing a suspected stroke or choosing the most appropriate care pathway in an emergency often takes only minutes, sometimes seconds. It is in these moments that physical distance between those on the scene and specialist expertise can be overcome through telemedicine.

This approach, however, takes shape in markedly different ways in the two countries. In the United Kingdom, telemedicine is mainly used to support rapid decision-making in clearly defined scenarios, such as stroke. It does so by directly connecting ambulances or emergency departments with specialist physicians. In the United States, by contrast, telemedicine is embedded in broader models that address the overall organization of emergency services, with a strong focus on system sustainability as well.

United Kingdom: telemedicine as an accelerator for stroke care pathways

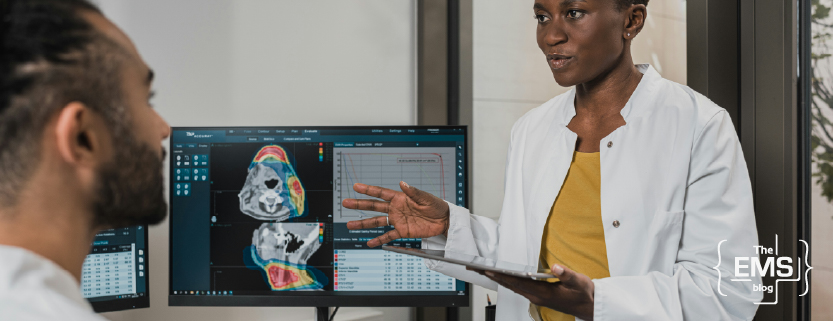

The most well-documented and easily understood use case of pre-hospital telemedicine in the United Kingdom concerns acute stroke. During the pandemic, pilot projects were launched in areas such as North Central London and East Kent involving pre-hospital video triage, meaning real-time clinical assessment via video directly from the ambulance. In practice, paramedics in the field connected live with a neurologist, who supported the evaluation before hospital arrival.

The objective was highly practical: to reduce errors in stroke identification—many conditions can present with similar symptoms—and to direct patients immediately to the most appropriate facility, avoiding unnecessary steps or delays.

According to evaluations conducted by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and the Nuffield Trust, the scientific evidence is still evolving and does not yet allow for definitive conclusions regarding clinical outcomes or costs. However, in everyday practice, the model has been deemed usable, safe, and acceptable by the professionals involved.

One key finding is that the use of telemedicine did not slow down ambulance on-scene times compared with traditional pathways. At the same time, a clear critical issue emerged: for the system to function effectively, there must be genuine availability of specialists—someone must actually be ready to respond on the other side of the screen.

The national framework and the limits of telemedicine in the UK

This approach fits within a broader national strategy. The English model for stroke care, based on integrated networks linking community services, emergency departments, specialist centers, and rehabilitation. It explicitly provides that the pre-hospital phase can also be supported by telemedicine. The aim is to identify as early as possible those patients who may benefit from advanced treatments, such as thrombectomy, and to transport them directly to a center capable of delivering such care, avoiding intermediate stops.

At the same time, NICE guidelines—the body responsible for assessing the effectiveness of healthcare practices in the UK—adopt a cautious stance when moving beyond highly structured pathways such as stroke care. For “undifferentiated” medical emergencies, namely calls to the 999 emergency number, NICE notes that there is not yet solid clinical evidence. At present, clear benefits of immediate remote clinical support in terms of outcomes or costs have not been demonstrated. For this reason, it does not issue binding operational recommendations but encourages further rigorous studies and evaluations. It also clarifies that where such services are already in place, they should not be discouraged, but systematically monitored and assessed.

A fairly clear picture emerges. In the United Kingdom, telemedicine works best when it strengthens already well-organized pathways where time is a decisive factor, as in the case of stroke. It appears less mature as a general-purpose tool applied indiscriminately across all pre-hospital emergency care.

United States: telemedicine as an organizational and economic lever

In the United States, the approach is different and more oriented toward the overall transformation of emergency services. The federal framework on telemedicine for EMS and 911 describes these programs as systems that enable dispatch centers, field crews, healthcare professionals, and citizens to interact in real time. These systems allow information to be shared throughout the entire process, from the emergency call to the final decision. That decision may involve on-scene treatment, transport to a hospital, or referral to an alternative facility.

Here, telemedicine addresses two very concrete needs. The first concerns decision quality: allowing crews rapid access to medical expertise and reducing the risk of unnecessary or inappropriate interventions. The second is structural and economic. As reported by the Federal Interagency Committee on EMS, for many years in the United States reimbursement for emergency services was almost exclusively tied to transport to the Emergency Department (ED). This created a systemic incentive to convey nearly everyone to hospital, even when it was not the most appropriate solution.

The ET3 model

It is within this context that the ET3 model (Emergency Triage, Treat, and Transport) was developed, a pilot program of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Innovation Center. ET3 introduces new reimbursement mechanisms that allow emergency services to be paid not only for transport to the emergency department. Emergency services can also be reimbursed for transport to alternative destinations, such as primary care facilities or mental health services, as well as for treatment provided on scene. Within this framework, telemedicine becomes a key enabling tool, allowing a healthcare professional to assess the situation remotely and support decisions other than automatic hospital transport.

In the U.S. context, complex issues come into play, such as physician licensure across state lines, professional liability, variability in regulations among federal states, and a regulatory framework that is still evolving. As a result, the adoption of telemedicine in emergency care is often uneven, driven more by local programs or pilot initiatives than by a single, cohesive national strategy.

Two models, one shared direction

Comparing the two countries highlights a clear yet complementary difference. In the United Kingdom, pre-hospital telemedicine finds its most convincing role when it reinforces well-defined pathways, where rapid decisions about destination and priority are essential. By contrast, in the United States, telemedicine is conceived as a tool to rethink the entire functioning of emergency services. It reduces automatic reliance on emergency departments and promoting more guided and appropriate clinical decision-making.

Across both systems, telemedicine in emergency care serves to shift the center of gravity of emergency response: fewer automatisms, more clinical assessment, stronger networks. It works when embedded in a clear organizational structure, with genuinely available professionals, defined responsibilities, and measurable objectives. It is precisely in this space—between decision and time—that distance ceases to be the primary problem.

Follow The EMS Blog for more insights.